Sailing against the odds, the German East Asia Squadron made it from their base in China across the Pacific to neutral Chile. There, they inflicted upon Great Britain its first naval defeat in over 100 years.

However, the tide was still against East Asia Squadron, as the British were not going to take the defeat lying down. The fate of East Asia Squadron would be decided in the next showdown with the British fleet: The Battle of the Falkland Islands.

Background

On November 3, 1914, three of East Asia Squadron's cruisers (SMS Scharnhorst, SMS Gneisenau, and SMS Nürnberg) entered Valparaíso harbor, where they were welcomed by the local German-speaking population.

However, the squadron's commander, Maximillian von Spee, was in no mood for revelry. Despite his resounding victory over the British squadron sent to destroy him two days earlier, he was still pessimistic about his chances of making it back to Germany alive. When presented with a bouquet of flowers by the grateful German people, he declined them, commenting that "these will do nicely for my grave".

|

| SMS Scharnhorst, flagship of East Asia Squadron |

After leaving Valparaíso the next day, East Asia Squadron received two pieces of bad news. First, one of their cruisers, the SMS Emden, which had recently been sent to the Indian Ocean on a commerce raiding mission, had been caught by the Australian Royal Navy and destroyed. Second, East Asia Squadron's home port in Qingdao, China, had fallen to the Japanese.

Spee and his officers soon met to discuss what to do next. Most of the officers still wanted to make a run to Germany, but their ships were low on ammunition and badly in need of maintenance following the Battle of Coronel. Spee agreed, but he insisted (against the objections of his captains) on first raiding the British fueling base at Stanley harbor in the Falkland Islands before setting sail for Germany.

|

| Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee, commander of the second British naval squadron sent to destroy East Asia Squadron |

Meanwhile, the British were organizing their response to the defeat at Coronel. Having recovered from the initial shock of the loss, the British Admiralty dispatched the battlecruisers HMS Invincible and HMS Inflexible, two of the most advanced combat ships in the world, to the Falkland Islands under the command of Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee. There, they met up with other British cruisers, giving Sturdee a formidable complement of warships:

- HMS Invincible (flagship)

- HMS Inflexible

- HMS Glasgow (survivor of the Battle of Coronel)

- HMS Bristol

- HMS Cornwall

- HMS Kent

- HMS Macedonia

- HMS Carnarvon

Additionally, HMS Canopus, an outdated battleship that had been a part of Vice Admiral Cradock's squadron but had not participated at the Battle of Coronel due to mechanical issues, was beached at Stanley harbor to be used as a makeshift shore defense battery while the rest of the squadron laid in wait in the harbor.

Once the battle group was assembled, British Intelligence cryptographers sent out a fake signal which indicated that Stanley harbor was devoid of any armed British naval presence, suggesting the base was defenseless. It was this signal that convinced Spee that Stanley harbor was a prime target to raid, essentially serving as bait that would lure East Asia Squadron into a British trap.

The Battle of the Falkland Islands

On December 8, Spee made his move. That morning, he sent two of his cruisers, Gneisenau and Nürnberg, to approach Stanley harbor. Spee had no idea about the presence of Sturdee's squadron in the harbor, which was at anchor at that time and not expecting combat.

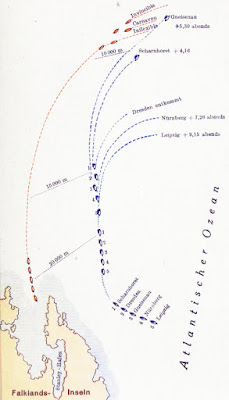

|

| German map of the Battle of the Falkland Islands |

While East Asia Squadron had caught the British fleet unprepared, it was an encounter that the Germans were not expecting, and Spee's cruisers soon received fire from an surprising source: The beached Canopus. This unanticipated resistance gave the German cruisers pause and kept them at bay while Sturdee's squadron prepared for battle.

Once Spee realized that he was outnumbered 7-5 in terms of main warships (including two British battlecruisers, the most powerful warships afloat at the time), he ordered his force to make a desperate dash out into the open ocean, where he hoped to lose the British ships. Unfortunately for East Asia Squadron, not only were the British ships faster, but the seas were calm and it was still morning, giving them plenty of daylight to work with. At 10:00, the British fleet left port and gave chase.

|

| The Invincible and Inflexible give chase. Painting by William Lionel Wyllie. |

At 1:00, the Invincible and Inflexible opened fire on East Asia Squadron. Realizing he couldn't outrun the British, at 1:20 Spee ordered Scharnhorst (his flagship) and Gneisenau to turn and fight, in an effort to give the other ships an opportunity to escape.

Scharnhorst and Gneisenau proceeded to exchange fire with Invincible and Inflexible. At first, the German ships managed to land several hits on Invincible, but the damage was minimal. Before long, the British battlecruisers began striking major blows against their German adversaries. The East Asia Squadron flagship Scharnhorst sustained several hard hits and began to list heavily at 4:04. At 4:17, she sank with all hands, including Spee. Gneisenau continued to fight on until her ammunition ran out at 5:15. Sturdee ordered a cease fire at 5:50, and the Gneisenau's crew allowed her to sink at 6:02, of which 190 were rescued by the British.

|

| The Scharnhorst sinks while the Gneisenau fights on. Painting by William Lionel Wyllie. |

Meanwhile, Sturdee dispatched Kent to run down Nürnberg, and Glasgow and Cornwall were sent to chase Leipzig. At 5:00, the Kent caught the Nürnberg, at which point the Nürnberg turned to fight (the slower Cornwall lagged behind). The two ships exchanged fire until 6:35, when the Nürnberg sustained so much damage she could no longer fire. The Nürnberg sank at 7:26; only twelve of her crew were rescued by the Kent.

Earlier, at 2:40, Glasgow caught up to the Leipzig and began firing. Leipzig responded with fire of her own, and both ships were damaged. Glasgow temporarily retreated, regrouping with Cornwall and Kent before re-engaging Leipzig. Leipzig fought on until 7:20, at which point the captain ordered the crew to scuttle the ship. At 9:05, Leipzig sank; only eighteen men were rescued. The Battle of the Falkland Islands was over.

|

| The Inflexible rescues survivors from the Gneisenau |

The Battle of Más a Tierra

Of the five cruisers of East Asia Squadron, only the Dresden successfully evaded the pursuing British ships and escaped destruction. The Dresden would remain at large until March 14, 1915, when she was cornered by the Glasgow, Kent, and Orama at Cumberland Bay, Chile.

In the short Battle of Más a Tierra, the Dresden briefly exchanged fire with her pursuers before the crew scuttled her and escaped to shore, where they would spend the rest of the war in Chilean captivity. Such was the end of East Asia Squadron.

|

| The Dresden, pictured here in Cumberland Bay just before her crew scuttled her. Note the white flag flying on the foremast. |

Interestingly, the Dresden and the Glasgow were the only two ships to take part in all three battles of the East Asia Squadron campaign, with the Glasgow being the only ship to survive all three engagements.

Aftermath

With the destruction of East Asia Squadron, Germany no longer possessed any major overseas naval forces. From that point on, direct naval action between German and Allied warships would be restricted to the waters around Europe.

Following his victory in the Battle of the Falkland Islands, Sturdee quickly rose through the ranks of the British Admiralty, becoming a full Admiral on May 17, 1917. He would command his own squadron at the Battle of Jutland (the largest naval battle of World War I) and retire as Admiral of the Fleet on July 5, 1921.

|

| Scan-generated image of the SMS Scharnhorst wreck. Note that the barrels on the forward turret are fully elevated, indicating she was firing as maximum range when she sank. |

On December 9, 2019, the wreck of the Scharnhorst was discovered, resting about 98 miles southeast of Stanley at a depth of 5,280 feet.

My Take

The story of East Asia Squadron is an interesting one to me. This motley collection of warships, cut off and half a world away from their home, nearly made it all the way back, inflicting a major defeat upon the world's most powerful navy (the first in over 100 years) along the way. Had it not been for Spee's single mistake of choosing to raid the Falkland Islands instead of sailing straight to Germany, East Asia Squadron may have done the impossible and made it all the way back to home.

That, I believe, is worth remembering.